Should we legalise doping in sports?

- Murphy Xi

- Nov 29, 2024

- 6 min read

Updated: Nov 29, 2024

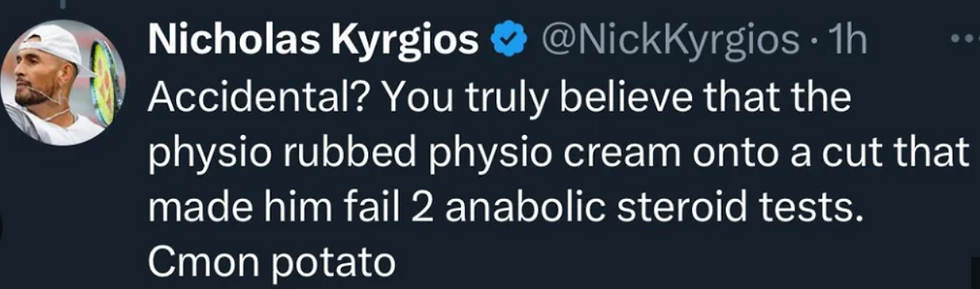

On Thursday 26 September, the World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) lodged an appeal to the Court of Arbitration for Sport (CAS) attempting to ban current tennis world number one Jannik Sinner for two years after he had twice tested positive for clostebol, a prohibited substance, in March 2024. However, Sinner was found by an independent tribunal of the International Tennis Integrity Agency (ITIA) to bear no fault or negligence for the dope, as tests revealed that his bloodstream contained less than a billionth of a gram of clostebol, which he claimed to be a result of contamination through his physiotherapist. The handling of the case sparked mass controversy, especially in the tennis world, with harsh criticisms coming from multiple-time slam champion Simona Halep and Australia’s favourite, Nick Kyrgios.

“I was judged completely differently, and I suffered a lot. I waited a lot, which I don't find fair at all.” ~ Simona Halep

“Ridiculous, whether it was planned or accidental… Massage cream…. yeah nice." ~ Nick Kyrgios

The realm of professional sports is no stranger to doping scandals. It seems inevitable that in every Olympic cycle, countless athletes are accused of taking performance-enhancing drugs. Instead of celebrating the incredible achievements of sports players, fans are often left questioning whether the athlete was legitimate. And whilst the WADA claims it maintains fairness, its enforcement of anti-doping regulations across various sports remains inconsistent.

This begs the question: why does doping remain a prominent issue across all sports in the status quo? And if, as it presently seems, there is evidence that this narrative is changing, what can we do moving forward?

Historic Doping in Sports

To understand why doping remains a perennial issue, it’s important to understand that historically it has been just as prominent. Most infamously, in the 1990s, Major League Baseball (MLB), the NBA, and NFL equivalent of baseball in the US, found itself in an era now known as the ‘Steroid Era’, casting a permanent shadow over the sport’s reputation. At its core, some of the sport’s most celebrated players - the likes of Mark McGwire and Sammy Sosa - were caught under the influence of anabolic steroids and other performance-enhancing drugs. Most evident in the 1998 home run race, McGwire and Sosa both smashed Roger Maris’s long-standing home run record of 61 set three decades earlier, with McGwire ultimately hitting an unspeakable 70 home runs. However, this power surge began to fade as more fans began to cast doubts over the legitimacy of the MLB’s stars, most notably seen in the 1994 players’ strike which deeply damaged the sport's credibility. During this period, many players saw their physiques drop drastically, which only fuelled the narrative that PEDs were driving their success. Jose Canseco’s release of his book ‘Juiced’ in 2005 exposed many players of the Steroid era, claiming that up to 80% of all MLB players were using steroids in the 1990s, directly naming players like McGwire.

Another interesting case is once-iconic cyclist Lance Armstrong, who won an unprecedented seven consecutive Tour de France titles between 1999 and 2005, an achievement so impossible that it resulted in persistent doping allegations during his career. After an investigation by the United States Anti-Doping Agency in 2012, these allegations were verified, and he was banned from Olympic sports for life and stipped of all seven of his Tour de France titles. Interestingly, in a 2013 Oprah Winfrey interview, Armstrong admitted, for the first time, to using banned performance-enhancing drugs for years, noting that he did so to remain competitive on the track.

“The definition of ‘cheat’ is to gain an advantage on a rival or foe that they don’t have. I didn’t view it that way. I viewed it as a level playing field.” ~ Lance Armstrong

And undoubtedly so, he was correct, as during the seven years that Armstrong won the Tour de France, 20 out of the 21 top three finishers were also found to have doped at some point in their careers. Armstrong was also found to have pressured his teammates into doping, threatening their positions on the team if they did not follow.

“He was not just a part of the doping culture on his team, he enforced and re-enforced it” ~ USADA (agency)

Thus, this scandal revealed just how extensive doping is within professional sports, where athletes find ways, both legal and illegal, to gain a competitive edge on their rivals, or as Armstrong puts it, “to remain competitive”.

Current Trends in Doping

Unfortunately, it seems that such a trend has not diminished, but rather accelerated over time. Whilst the WADA reported 1340 positive tests in 2000, this figure rose to 1736 in 2015. 28 more athletes faced sanctions for doping-related offences during the 2020 Tokyo Olympics than in the 2016 Rio Olympics, mostly notably resulting in the stripping of 51 medals from Russia and its international ban from sporting events. A 2019 study from the New York Times estimated that as many as 30% of all professional athletes are involved in doping. Primarily, this trend can be attributed to the inconsistency of testing standards across sporting principles: whilst the WADA sets out guidelines for its suggested doping regulations, it is often interpreted and implemented differently by individual sporting federations. In 2021, the Union Cycliste Internationale, the governing body for cycling reported that 2572 doping controls were conducted, but not all other sports have similar testing frequencies and protocols, leading to some athletes being tested more rigorously than others across sports. Additionally, doping technology is advancing faster than anti-doping agencies can keep up, with an exponential increase in the use of designer drugs and gene doping, methods that evade traditional testing mechanisms. For example, the 2016 Rio Olympics saw a rise in the use of synthetic erythropoietin in small doses to avoid detection, methods which are only being discovered presently nearly a decade later.

It’s markedly clear that, by now, the WADA can only be seen as a mitigative body rather than a preventative body. Instead of aiming to ameliorate the use of PEDs, its present goals seem to centre around punitive bans and deterrence; methods that have not worked. So what can we do moving forward?

One common perspective is that the use of PEDs should be entirely legal. If it is true that the use of PEDs is so commonplace and disastrous to the reputation of sports, then it can be plausibly claimed that allowing athletes to use steroids under regulation would fix the issue. At face level, it seems beneficial as well: if some athletes are already taking PEDs and gaining an unfair advantage over athletes who choose not to, then this would level the playing ground for all competitors.

Stemming from this concept, the ‘Enhanced Games’ has emerged as an Olympic-type competition that allows (and even encourages) its athletes to take performance-enhancing drugs without any WADA restrictions, aiming to test the boundaries of the human physique. The Games, set to take place in 2025, intends to “Celebrate the union of athletic excellence and scientific achievement,” and will be a unique and entertaining event for many curious watchers worldwide, eager to witness feats beyond natural limits. The games will redirect focus from doping scandals to athletic achievement and provide equal opportunity for athletes to maximise their performance level, something lacking in the current Games.

However, legalising the widespread use of PEDs poses significant health concerns, as overuse of these drugs can increase the risk of cardiovascular diseases, liver damage, hormonal imbalances and musculoskeletal injuries. Psychologically, PEDs can contribute to mood swings, aggression, and depression. Thus, the lack of limitations and ambition for glory make for an optimal breeding ground for misuse and abuse of PEDs, potentially leading to a cycle of dependency and health degradation.

“I will juice myself to the gills to win $1.5m prize in Enhanced Games” - James Magnussen (former Olympic swimmer)

Further, the seemingly ‘even’ playing ground that the Enhanced Games presents to athletes is not even at all, as athletes with better access and more money are able to gain an even clearer advantage over their competitors. More developed nations have access to more resources and more advanced technology, thus enabling them to develop substances that drastically set them apart from other, less developed areas of the world. This would lead to domination by athletes from wealthier nations, an imbalance that undermines the spirit of fair competition and compromises the integrity of sports.

So at the end of the day, where are we left?

The ongoing debate over doping in sports is a multifaceted issue that seems to have no immediate fix. Stringent bans and testing are inconsistent across sports and unable to detect certain PEDs. Conversely, the legalisation and regulation of PED use threatens to exacerbate existing inequalities due to concerns surrounding access. Perhaps, the future of sports hinges on finding a middle ground between the two - one that is safe and fair - but also one that fundamentally embodies the purpose of sport: an epitome of human physical achievement.

Comments